Quartic point group operation: Difference between revisions

→Fitting the curves: maxima |

→Alegraic methods: delete |

||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

&&\cdots | &&\cdots | ||

\end{array}</math> | \end{array}</math> | ||

== Next steps == | == Next steps == | ||

Revision as of 17:35, 21 January 2025

The point group operation over quartic (or hyperelliptic [1]) curves (of degree four) is defined geometrically as follows. Let

be a quartic curve on the x-y plane of real numbers, the polynomial in x on the right having either the coefficient p>0 or at least two real roots counting multiplicity.

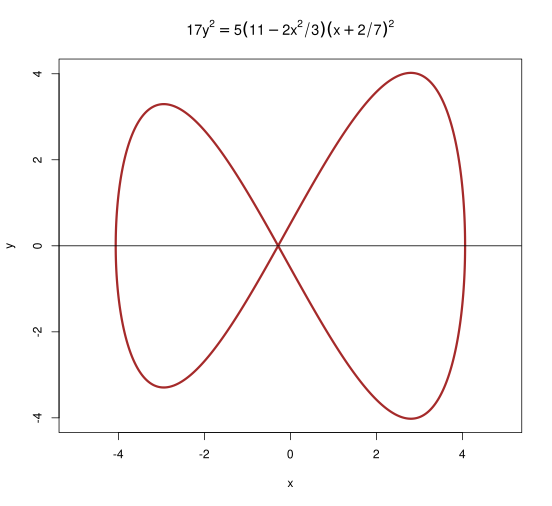

A quartic square dance

Every operation over a quartic curve will be defined geometrically by a “square dance” of the four points of intersection of the quartic curve and a parabola [2] whose axis is parallel to the y-axis, and otherwise to be determined.

Namely if P, Q, R, and S are four points of the quartic curve, through which a parabola with an axis parallel to the y-axis passes, then we will say that

where O is the additional “point at infinity” which serves as the additive group identity.

Additive inverses

If P is a point on the elliptic curve, then its inverse is found by solving for in this “square dance” equation

where the parabola is required to be tangent [3] to the curve both at the point P and at the unknown point Q. Simple algebra and calculus should yield a unique solution.

Point averaging

The average or “mean” of two points P and Q may be found by solving the square dance equation

Here let the parabola pass through the points P and Q and be tangent to the quartic curve at R. Take the inverse to find the mean: .

Point trebling

To treble a point P, solve the “square dance” equation

and then take the inverse of Q to find . Here the parabola is required to osculate [4] the quartic curve at the point P which appears with a multiplicity of three in the equation, and intersect simply at the point Q.

Point trisection

Trisecting a point is exactly the same as trebling, except that it is at the unknown point Q where the parabola and the quartic curve are required to osculate, and a simple intersection is permitted at the point P.

- .

Now take the inverse of Q to find .

Point doubling

Point doubling is performed by trebling and then averaging

- .

Point bisection

Point bisection or “halving” is performed by doubling a point and averaging with its additive inverse.

Point group addition

The most essential and basic operation of “adding” two points, which should serve as the point group operation for cryptographic purposes, is now derived at the end of a long, roundabout square dance routine by calculating the mean of two points, and then doubling by means of trebling and averaging.

The algebra and calculus equations should be simplified, and made as efficient as possible. The operation has been suitably defined, and nothing has been introduced here that should violate the axioms of an Abelian group.

Fitting the curves

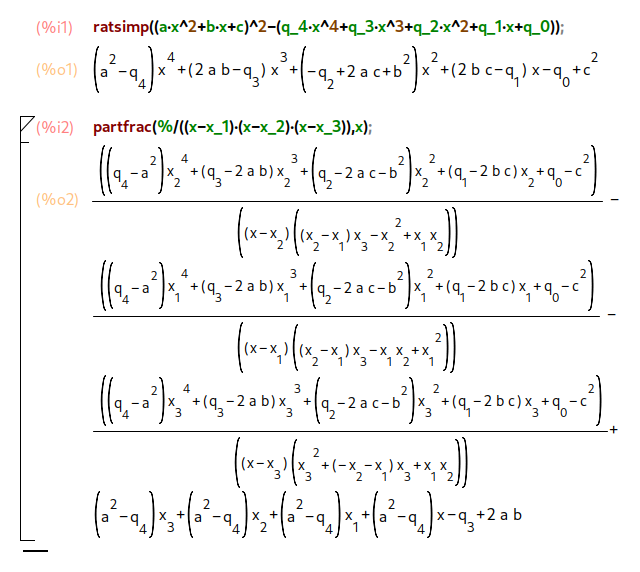

When the resolvent quadratic equation is squared and diminished by the equation for the quartic curve, and the leading coefficient of the resultant is set to one, after performing a partial fractions decomposition, we can start building a system of equations to determine the coefficients of the resolvent. The leading coefficient a is immediately determined.

Next steps

Once you have mastered the quartic point group operation, the proof of Mordell’s theorem by infinite descent, methods of bounding heights of rational numbers, and the theory of numerical and floating point approximations for curve fitting, you may move on to the quintic point group operation.

Appendix: R code for example curve plot

#! /usr/bin/R -f

H <- function(x){

sqrt((5/17)*(11-2*x^2/3)*(x+2/7)^2)

}

xvals <- seq(0,sqrt(16.5),0.0001)

plot(x=c(xvals,rev(xvals),-xvals,-rev(xvals)),

y=c(H(xvals),-H(rev(xvals)),-H(-xvals),H(-rev(xvals))),

type="l", lwd=3, col="brown",

xlab="x", ylab="y", asp="1",

main=expression(17*y^2 == 5*(11-2*x^2/3)*(x+2/7)^2)

)

abline(0,0)

- ↑ https://hyperelliptic.org/

- ↑ Borrowed perhaps from Category:conic section cryptography but that is another matter.

- ↑ Latin for “touching.”

- ↑ Latin for “kiss.” The y-coördinate and the first and second derivatives must be equal for the two curves which are said to osculate at that x-coördinate.