Quintic point group operation

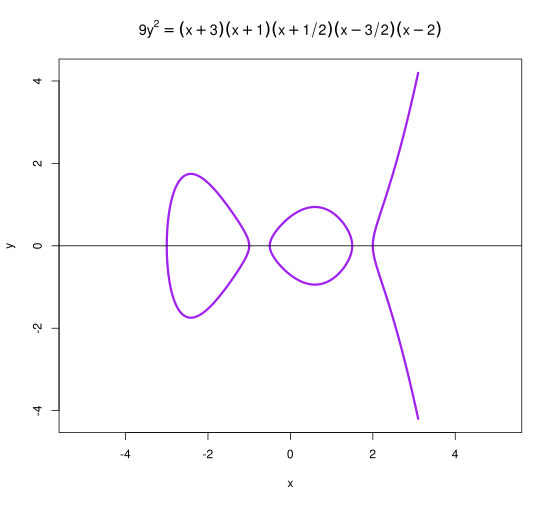

Suppose we have a quintic curve in the form

- .

Through any four points on a quintic curve in this form, an ordinary elliptic curve in the form

may be fitted, and this elliptic curve must intersect the quintic curve at a fifth point, uniquely determined, up to sign of the y-axis.

The quincunx equations

If P, Q, R, S and T are the five points of intersection between the quintic curve and the fitted elliptic curve, permitting multiplicity, let

- ,

where O is the additional “point at infinity” considered to lie on the curve and serve as an identity for its additive point group operation.

Curve fittings through one point

Choose a point P and solve , , and by curve-fitting. Now , , , and .

Curve fittings through two points

Choosing points P and Q it is possible to solve for and by curve-fitting: and , if scalar division is permitted. Also and so and , etc.

Goals and objectives

The goal is to reach the point from the point P alone, and to reach the point from the points P and Q if possible, and if so, by the shortest possible path of computation, i.e., using the least number of elliptic curve fittings.

Point averaging and limit

Point averaging is possible.

- .

A closed form expression also exists for

although, apparently not for the point group “sum” itself. The only remaining option then is to approximate

using only those rational numbers n for which a closed form expression exists for the rational scalar multiple by n of the point group “sum” we are calculating.

Insolubility in closed form radicals

It has been known for over 500 years that unlike quartic equations, general quintic equations cannot be solved in closed form radicals, and that is indeed what we find here for the point group operation which we have defined by “summing” five points that intersect an elliptic curve to an additive identity “point at infinity.”

Numerical methods

Numerical or what we call “floating point” methods are generally used in practice to solve equations in the fifth or higher degree. The point averaging method, which is expressible in closed form, certainly allows the solution to be approximated to any desired degree of accuracy.

Exact solutions from floating-point computations

If the point group operation as defined does indeed map pairs of rational points on the curve to rational points on the same curve not exceeding a given denominator or height, then floating point approximations of sufficient precision can potentially be proven adequate to rigorously determine the exact numerators and denominators of those rational points.

If we had anything else to offer in this regard, we would have succeeded in doing exactly what the classical Italian mathematicians already proved impossible centuries ago.

R code for example plot

#! /usr/bin/R -f

H <- function(x){

sqrt(1/9*(x+3)*(x+1)*(x+1/2)*(x-3/2)*(x-2))

}

xvals <- seq(0,3.1,0.0001)

plot(x=c(rev(xvals),-xvals,-rev(xvals),xvals),

y=c(H(rev(xvals)),H(-xvals),-H(-rev(xvals)),-H(xvals)),

type="l", lwd=3, col="purple",

xlab="x", ylab="y", asp="1",

main=expression(9*y^2 == (x+3)*(x+1)*(x+1/2)*(x-3/2)*(x-2))

)

abline(0,0)